The Great Salt Lake is shrinking and we only have ourselves to blame. That’s the message of a new white paper released by Utah State University last week.

The water level of the Great Salt Lake is constantly fluctuating, both seasonally and from year to year as we cycle through periods of wet and dry, but that’s all just background noise to a distinct drying up trend over the past 150 years.

Craig Miller, an engineer with the Utah Division of Water Resources, created a virtual model of the Great Salt Lake for the paper -- a hypothetical version of what the lake would look like today if we hadn’t been drawing it down since the days of the state’s pioneers.

He calls this hypothetical level, the “natural” Great Salt Lake level. To figure out how much water would be in the lake, they started with historic lake levels from 1847. “We continued to add flows into the virtual lake equal to the amount of human depletions estimated for that year,” says Miller.

After adding that water back to the lake year by year, the virtual untouched Great Salt Lake is 11 feet higher than the lake that’s actually sitting out there at one of its lowest levels in modern history. I asked Craig Miller to translate that into volume for me:

Today’s volume is about 9 million acre feet. At 4204.5 feet, which is the elevation of the surface of the lake with that extra 11 feet, the lake’s volume would be over 19 million acres. That’s an increase of 48%. “The volume would be close to double,” he says.

So, what do we learn from thinking about what the lake would look like without human interference? “Haven’t you always wondered what the lake would be like without humans here,” Miller asks me. I tell him that I have. “Me too,” he says, “This was a really fun project because it answered a lot of questions I’ve always had.”

But more than a fun math problem, this paper has some very real warnings.

Climate reconstructions have shown that there hasn’t been any dramatic decrease in natural water supply to Great Salt Lake over the past century and a half, so the lake is half the size it’s supposed to be solely because we’ve used that water on our lawns and fields and evaporation ponds instead.

A dried up Salt Lake would spell dangerous dust storms for the Wasatch Front and dry up over a billion dollars in annual income to the state. It would also be disastrous for millions of migratory birds.

But, if you’re not a birder or a brine shrimper, why should you care that the lake is half dried up?

“I think a lot of Utahns benefit from the lake without even knowing it,” says Josh Palmer, spokesperson for the Utah Division of Water Resources.

“Someone may not think a lot about the Great Salt Lake, but they love skiing and snowboarding in Utah. Well, the lake effect has a positive effect on our snowpack, so if you love powder, you should care about the Great Salt Lake. Some may not think about the Great Salt Lake itself but they love the variety of birds and other wildlife we see around the lake, so if you care about wildlife you should care about the Great Salt Lake. Some people don’t think about the Great Salt Lake, but they care about Utah’s economy. Well, the lake contributes a lot via recreation, brine shrimp, mineral extraction to Utah’s economy, so if you care about the economy, you should care about the lake.”

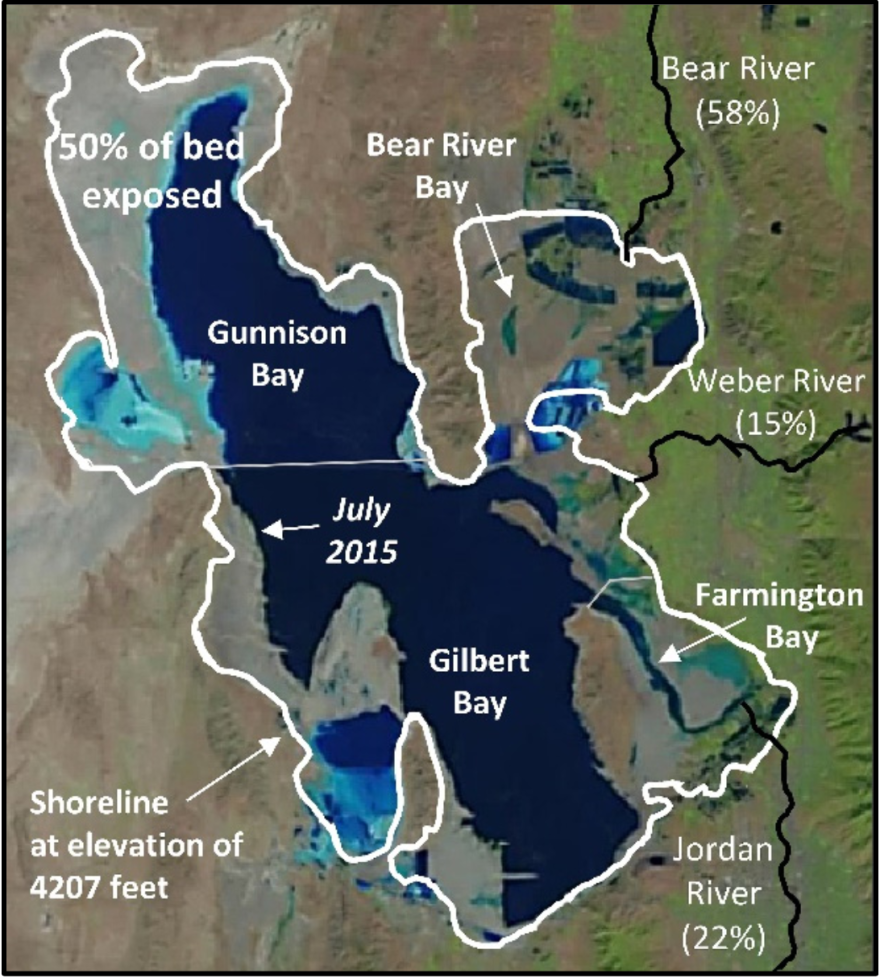

On the day that this white paper on the Great Salt Lake was released, Senate Bill 80 was heard by the Utah House Revenue and Taxation Committee. This is a bill that would take tax dollars currently reserved for transportation projects and set it aside instead for water infrastructure projects: Three projects specifically, one of which would divert more water out of the Bear River so that even less of it reaches the Great Salt Lake.

“It would be used as part of a solution to help meet the needs of a growing population,” says Palmer. “The water from Utah’s allocation was once projected to be needed in 2015, but due to conservation, agricultural conversions and other efficiency projects, it’s now not projected to be needed until 2040 or beyond.”

This Bear River Development Project is estimated to decrease the lake level by another eight and a half inches.

Senate Bill 80 passed out of the House Taxation committee and several committees before that. It’s on its way to a floor vote and if it passes, there will be a fund with a couple hundred million dollars in it, earmarked for developing the Bear River, which according to the Division of Water Resources, isn't going to happen anytime soon.

If we can hypothesize a lake without humans, we can hypothesize a Utah without politics, so SB80 aside and the Bear River Development Project aside, what can be done to help turn the downward trend of the lake around?

“We hope this starts a conversation,” says Palmer. “We hope that skier or that person who cares about the economy or the wildlife on the lake, will not only look into what’s happening with the lake, but look into how they can be part of the solution instead of part of the problem.”

But you have to care about the lake in the first place, or else the warnings in this paper are completely lost. So, Palmer says the Division of Water Resources wants to tie these facts to things people already care about.

“I grew up in Syracuse and I could ride my bike to the Great Salt Lake. I innately, because it’s part of where I grew up, care about the lake. There are people only know about the smell or the brine flies. They don’t understand that a lot of the things they already care about are better because of the lake.”