The mopane worm, named because it feeds primarily on the leaves of the mopane tree, isn’t actually a worm.

“A mopane worm is the colloquial name of a caterpillar. That is, the immature stage of a very beautiful moth in a family called the Saturniidae," said Barbara van Asch, a senior lecturer in the genetics department at Stellenbosch University, who specializes in insects.

She’s studied many species, from weevils to parasitoid wasps, and of course lepidopterans, like butterflies and their caterpillars. Most of which have a period of dormancy and emerge under favorable conditions, but some, like the mopane worm are ‘outbreak species.’

“That means that when the conditions are favorable, the populations explode, and the eating of the leaves is so intense that it can be heard, and the amount of frass, that's droppings that they produce, creates almost like a rug, a carpet under the trees," said van Asch. "So, they eat massively. They can eat as much as the population of elephants in the same area.”

And though they leave swathes of defoliation, the mopane trees regrow a second flush after the caterpillars burrow to pupate in the ground. It turns out, this whole process is heavily mediated by rain.

“So, in the past few years, we've had fewer numbers, because we've been under a severe drought, the whole of Southern Africa has," said van Asch. "And everybody eats these caterpillars, birds, animals, and humans.”

Humans harvest mopane worms in the millions. Degutted, boiled, dried, and seasoned, they’re a highly nutritious source of high-quality protein and a source of income for many in an industry valued at over 85 million US dollars.

“It's only westernized societies that see eating insects as something that has a yuck factor. Two thirds of the world population will consume insects on a regular basis, and it's part of the culture and the food traditions in the whole of Africa, in the whole of South America, in most of Asia,” said van Asch.

So, insects can be economically significant and an important part of a healthy diet. And mopane worms are the most harvested wild edible insect of southern Africa.

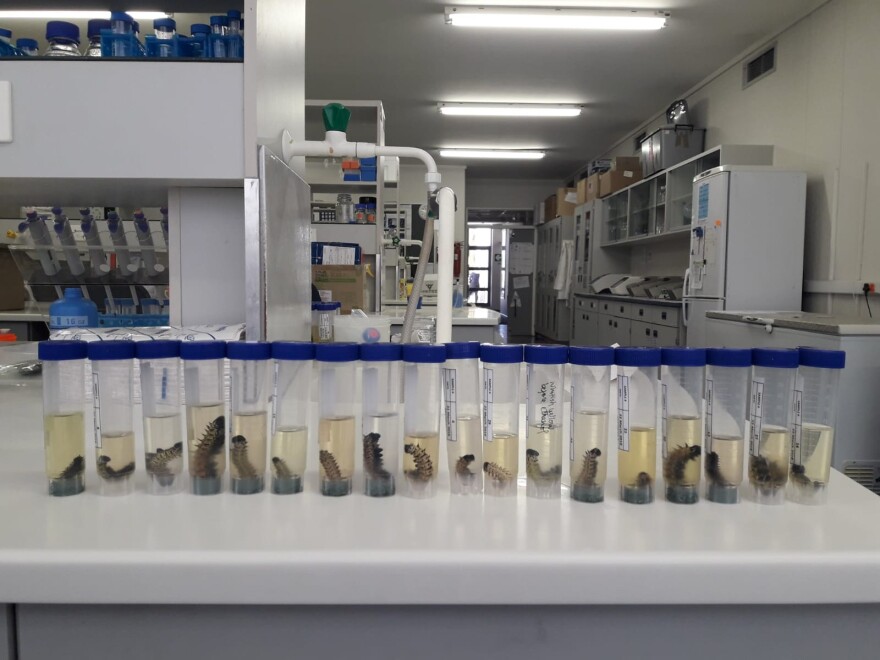

Provided that, it makes sense that van Asch and her team would look at their DNA in the first ever study to assess their genetic health and population structure.

“So, what we found in the populations that we studied is that the populations seem isolated, that there's lack of gene flow,” she said.

This can be good or bad. With a fragmented habitat and isolated populations, it could mean the preservation of local adaptations, but isolated populations are more vulnerable to genetic drift and inbreeding.

“It is very useful to identify hot spots of biodiversity, and that includes particularly high levels of genetic diversity that we protect as insurance against extinction,” said van Asch.

Which is important given the specie’s significance and the reality that some of these populations may be lost.

“We cannot protect everything. We just don't have the means," said van Asch. "And Southern Africa, it's a huge region, and even if we subdivide the region in smaller areas, it's still over more, overwhelmingly huge. So, we need to prioritize what to protect and how and when.”

And that process starts with knowing what types of diversity exist and where, for all species really: from elephants to trees to caterpillars.